It’s officially summertime, and here at the ODNP, one of our favorite things about this glorious season in the Pacific Northwest is visiting Crater Lake without the hindrance of snow. Not only do the lake and surrounding landscapes provide breathtaking views and recreational enjoyment; historic newspaper communications played a significant role in advocating for the preservation of the lake and the creation of Crater Lake National Park.

High along the crest of the Cascade Mountain Range in southern Oregon, the magnificent blue lake sparkles as a symbol of both geological and cultural change. The Native American nations of the region, including the Takelma, Upper Umpqua, Molala, and the Klamath people, descendents of the Makalak Nation, have many stories about the formation and existence of the lake, all of which portray the site as a venerable place of great and often dangerous power.

Crater Lake was created by an ancient volcano, now known as Mount Mazama, that once reached a soaring height of 12,000 feet, slightly taller than Mount Hood (11,240 feet) but not quite as tall as Mount Shasta (14,179 feet). Approximately 7700 years ago, Mt. Mazama erupted violently, spreading volcanic debris all over Oregon and leaving a huge caldera where the mountain once stood. Over about 750 years, the crater filled with rainwater and snowmelt to form the deepest lake in the United States – 1943 feet deep – at about five by six miles wide. Legends indicate that Native Americans witnessed the eruption of Mt. Mazama and have known about the lake ever since, but early European explorers and traders were never told about the lake because it was believed to be sacred.

No rivers flow into or out of Crater Lake; it is completely contained, and evaporation and precipitation continually refresh the lake’s water supply, making it the cleanest water in the world. Later volcanic eruptions formed Wizard Island, the signature landmark that rests in the west side of the lake.

Europeans first set eyes on the brilliant blue water in 1853, but excitement about the “discovery” took a backseat to the urgency of the gold rush at the time. The first published account of the lake didn’t appear until about ten years later, when Chauncy Nye, leader of an exploratory expedition that stumbled upon the lake in the Cascades, submitted a descriptive article to Jacksonville’s Oregon Sentinel on November 8, 1862:

Dissemination of information about the lake’s location and striking appearance via Oregon’s early newspapers soon led others to explore the area, and word quickly spread about the lake’s intense beauty. In 1869, editor of the Sentinel, James M. Sutton, led another expedition to the lake and wrote an article for the Jacksonville newspaper in which he referred to the lake for the first time as “Crater Lake”:

In 1870, William Gladstone Steel , a young boy living in Kansas at the time, happened to see an article about Crater Lake in the newspaper page that had been used to wrap his lunch. The description fascinated him, and he promised himself that he would visit the lake someday. Steel and his family soon moved to Portland, Oregon, and he was finally able to visit Crater Lake 15 years after he first set eyes on the newspaper article. After viewing the lake for himself, his mind was made up to do whatever it took to preserve the lake as a public park. Steel was included in the first expedition to create a map of the lake in 1886, and he spent the next 16 years lobbying and rallying support for the preservation of Crater Lake.

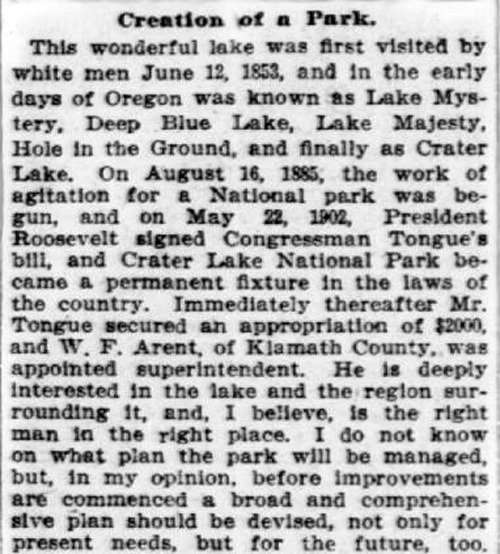

In 1893, the lake was included in the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, which offered some protection from mining and lumber interests, but Steel was not satisfied until Crater Lake was officially made into a National Park on May 22, 1902.

Discussions of building a road to Crater Lake began soon after, in order to improve accessibility to the natural wonder for all people to see. Controversy surrounding the Crater Lake road system can be traced through Oregon’s historic newspapers, with discussions of the pros and cons of building the roads and especially concerns about the monetary cost of the project:

The road construction effort proved essential to a greater scientific understanding of the lake, allowing geographers, botanists, and other researchers to visit and study the area:

Geological and ecological researchers continue to visit Crater Lake today, and thanks to the ease of access provided by roads, people from all over the world can enjoy the wonderful sights, hike the trails, swim in the lake, and go camping:

As the summer sun melts the accumulation of snow along the ridge of the Cascades, the temperature warms up and conditions for enjoying the outdoors at Crater Lake are ideal. Summer brings many opportunities, but a visit to Crater Lake is one of the most unique experiences that Oregon has to offer in the summer months. In the words of William Gladstone Steel, “father” of Crater Lake National Park:

Sources and additional information:

Crater Lake: History. National Park Service and U.S. Dept. of the Interior; Crater Lake National Park, 2010. Web. 29 June, 2012. < http://www.nps.gov/crla/planyourvisit/upload/2010-history.pdf >

Crater Lake Institute. Web. 3, July, 2012. < http://www.craterlakeinstitute.com/ >

Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. National Park Service and U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012. Web. June, 2012. < http://www.nps.gov/crla/index.htm >

Crater Lake Reflections: Visitor’s Guide. National Park Service and U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Summer/Fall 2012. Web. 29 June, 2012. < http://www.nps.gov/crla/parknews/upload/Crater-Lake-Reflections-Summer-Fall-2012-Low-Res.pdf >

Oregon Secretary of State. “Oregon Focus: Native American Legends: Crater Lake.” Oregon Blue Book. 2012. Web. 29 June, 2012. < http://www.bluebook.state.or.us/kids/focus/crater.htm >